Why Kit Marlowe now?

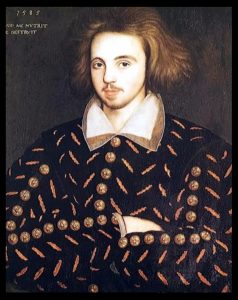

Christopher (aka Kit) Marlowe was born in 1564 and died dramatically in 1593. He was one of William Shakespeare’s most interesting contemporaries; they surely exchanged ideas around the playhouses and taverns. Marlowe was also close with others on the literary scene, including Thomas Kyd, Thomas Watson, and Thomas Nashe, as well as courtiers Thomas Walsingham, Sir Walter Raleigh, Thomas Harriot, and the Crown agents present when he died, Robert Poley, Ingram Frizer, and Nicholas Skeres.

Some may be familiar with recent stylometric studies that have revealed his hand at work in Shakespeare’s Henry VI trilogy. Others may have heard vague rumors that Marlowe was “really” Shakespeare (we believe he wasn’t). Historical documentation, however little there may be, suggests Marlowe was an Elizabethan spy, perhaps working both sides of the Catholic/Protestant fence. We are certain he was one of a group of educated young men living in London and trying their hands at becoming professional writers – a profession that wouldn’t have been possible without the then-recent advent of Gutenberg printing technology.

Marlowe was not only a brilliant poet who transformed blank verse into a “mighty line,” but also he pushed the boundaries of what could be said in a state governed by censorship. Satire and innuendo abound throughout his works, and his translation of Ovid’s Amores that included John Davies’ Epigrammes was named explicitly in the 1599 Bishop’s Ban (see McCabe, “Elizabethan Satire and the Bishop’s Ban“; Bennett, “Early Modern English Sati/yre“). Some have speculated that this ban targeted works featuring sexual subtexts, but the Bishops’ primary aim was to suppress satire.

Modern readers must remember that even subtle or satirical critique of Elizabeth I’s government, religion, or court was very often met with censure, or worse punishments like interrogation, torture, imprisonment, and/or a grisly death (we’ll get to Marlowe’s shortly). In 1590’s England, words and ideas were a matter of life and death. Just as now, propaganda frequently occluded the truth of people’s places in their worlds inciting fear, ire, and division. One had to be savvy about what they said and how they said it, lest it be misconstrued (or construed as one intended). The information revolution that spread through Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries gave rise to increased literacies, and subsequently, revolution, revolt, resistance, and seemingly unbreakable cycles of retribution.

Sound familiar?

As I’ve discussed elsewhere, the parallel explosions of information technology at the turn of the seventeenth century and the twenty-first offer an ideal opportunity to revisit the impact early modern print technology had on its readers. By positing the Gutenberg revolution as analogous to that of the Internet, students can make meaningful connections to better understand both the conditions of literary production in early modern England, and those of today.

But what happened to Kit? Whether a result of his reputation as a supposed atheist, his possible career as a spy, or an argument over a bar tab, he was killed by a Crown agent with his own dagger, thrust through his eye socket. The portrait of him hanging in the Master’s room at Corpus Christi in Cambridge features a black frame, a late-medieval/early modern convention signaling that an individual died in suspicious circumstances. “Suspicious” indeed!

What does the Kit Marlowe Project do that other websites don’t?

Our website has been built by undergraduate students to offer an accessible, open-access resource for Marlowe-curious individuals to learn about his life, works, and times. Simultaneously it is a site of knowledge-making in action. Here, students contribute the fruits of their research and scholarly labors from semester to semester. Each class creates content that their successors will not only study, but also fact-check, edit, revise, and update as new material is published online. Because this pedagogical model is both experimental and unique, we also offer blogs that document its inception and evolution, as well as teaching materials that we have used our classrooms. We invite our counterparts at other institutions to”try this at home” and invite contributions. Please contact us for more information.

Kristen Abbott Bennett, May 2018

The Kit Marlowe Project is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The Kit Marlowe Project is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.