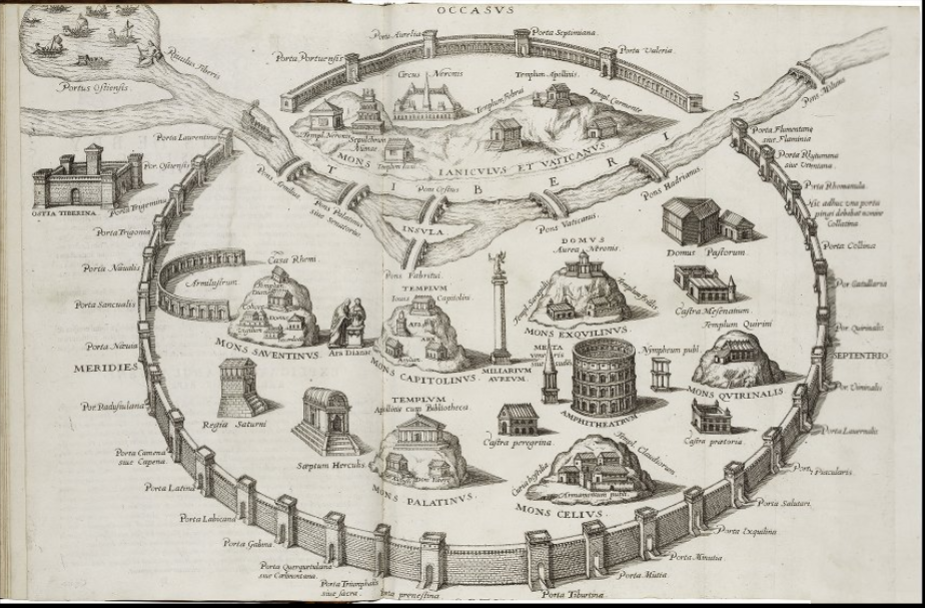

While Queen Elizabeth I ruled England, her person and government gave playwrights, pamphleteers, and others contributing to popular culture much fodder with which to debate the country’s ethics, religion, and politics. Of course, criticizing Queen and country was risky business. Rome emerges as a popular geographical foil for commenting upon the English political landscape, succession, social inequity, and the religious tensions that characterized the Reformation.

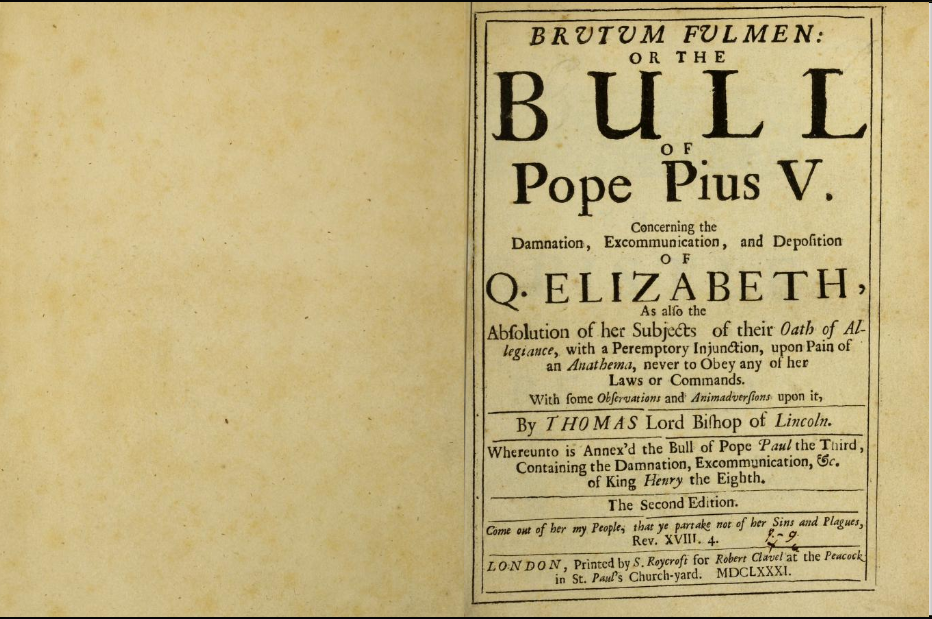

Rome was essentially the capital of Catholicism during Elizabeth’s reign. As head of the Anglican (later Protestant) church, Elizabeth was perhaps the most religiously tolerant Tudor ruler, but that was not enough for Catholic Rome. Although Elizabeth permitted Catholics to worship privately (unlike her sister Queen Mary who, when the situation was reversed, brutally killed hundreds of Anglicans earning her the name “Bloody Mary”), they were fined for not attending Anglican services, and punished without trial if suspected of plotting against her. The Tudors ruled under a theory of the divine right of kings (they were chosen by God to rule), but with each change in religion the subjects feared for their salvation after death and began to doubt the Tudor claim to the throne. The split between Anglican and Catholic religions caused Pope Pius V to excommunicate Queen Elizabeth I from the church in 1570. Pius V announced that it was not a mortal sin to kill Queen Elizabeth I, effectively pitting millions of Catholics against her. Plots against Elizabeth escalated from this point forward. Laws surrounding what could and could not be said about her reign became increasingly restricted, and some subjects began to think of her as a tyrant.

Because of the dangers associated with speaking ill of the monarchy, writers often juxtaposed England with Rome in order to avoid punishment while still commenting on topical events. It became a touchstone for political debates, art, politics, and military strategy. Roman mythology offers Elizabethan writers an opportunity to both mythologize their Queen, associating her with Cynthia, Diana, and Astraea, plus Rome offers the distance writers needed to critique the Queen and her court without the risk of punishment.

For example, Shakespeare’s plays Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus, and Titus Andronicus use the ideals of Rome and Romans in order to integrate the use of Roman history in English culture while also interrogating the role of the people under tyrannical rule in conjunction with the monarchy. Although many consider the above to be the “Roman plays,” Shakespeare uses Rome as a foil to criticize English politics, society, and religion in plays Richard III and Henry IV.