Edward “Ned” Alleyn (1566-1626) was an early modern London actor and founder of Dulwich College. He was known for his physical size and ability to handle commanding parts. Born in 1566, he was characterized as a “bred a Stage-player” and joined the Lord Admiral’s Men in London; Alleyn was famous for his roles in Christopher Marlowe’s plays Tamburlaine, Faustus, and The Jew of Malta. In 1592, Alleyn married Joan Woodward, Rose Theatre owner Philip Henslowe’s daughter. After retiring from the stage, Alleyn joined Henslowe as a business partner and their investments made him a wealthy man. He made a lasting impact off stage building and managing an orphanage, and founding the pensioners’ home called the College of God’s Gift at Dulwich. Today, this is Dulwich College. Following his first wife’s death, Alleyn married the daughter of John Donne, poet and dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Years later, Alleyn traveled with the intention of purchasing property, but on November 13, 1626 Alleyn would write out his last will and testament. He was buried two weeks later in the Dulwich College chapel.

The Babington Plot was an incident in which Anthony Babington and the Plough Group planned to assassinate Elizabeth I, install Queen Mary of Scots onto the throne, and restore Catholicism to England.

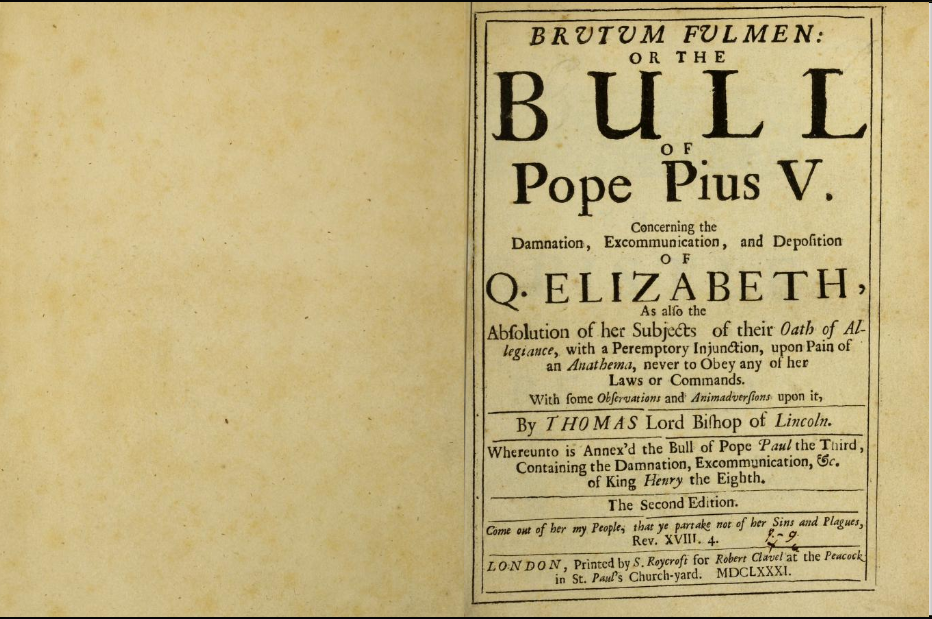

In 1570, Pope Pius V declared the Protestant Elizabeth a heretic, despite her relative tolerance towards Catholics throughout the kingdom. She was excommunicated via papal bull: “we do out of the fullness of our apostolic power declare the foresaid Elizabeth to be a heretic and favorer of heretics, and her adherents in the matters aforesaid to have incurred the sentence of anathema and to be cut off from the unity of the body of Christ” (Regnans in Excelsis). This authorization of Elizabeth’s metaphorical dismemberment was also taken literally by the Pope’s followers, some of whom sought to carry out this sentence.

What made the Babington Plot interesting to scholars is the fact that most of the intelligence came from not the conspirator – but the government. More specifically, Spymaster Francis Walsingham saw an opportunity to gather conspirators all at once by leading them to believe that they had a chance at actually vanquishing the Queen.

While dubbed “The Babington Plot,” by many scholars, Anthony Babington wasn’t the brains behind the operations; if anything, Babington serves as a scapegoat for the masterminds behind the plan.

Curiously, many feel that Babington was only half convinced that the plan had merit, or if it would work it all. While he had believed in the idea of bringing Catholicism back to England and felt that the Queen was too popular among her citizens, he did not spearhead this assassination plot.

His friend and co-plotter, Thomas Salisbury, urged Babington to stay away from the leader of the Plough Group, John Ballard, who subsequently devised the assassination plot.

Father John Ballard was a priest from Rheims College that had been working to squelch the anxieties that English Catholics felt towards Rome. Although Ballard was born in England, he studied at Rheims College and became a Catholic missionary (Nicholl).

Being a Catholic missionary was almost guaranteed to garner attention from the Church of England, so Ballard had several public different disguises. “Captain Fortescue” was one of his better-known aliases, and one he used in his attempts to de-throne the “heretic” Queen Elizabeth.

At Rheims, Ballard vowed to remove Elizabeth from power, and his supporters, including Gilbert Gifford among others, cemented his ambition. Around March 1586, Ballard hired John Savage to assassinate the Queen. This may have been the first step in a more complex plan to help Spain and other European Catholic allies take control of England.

In early 1586, disguised as his favorite alias “Captain Fortescue,” Ballard went to France to meet with Spanish Ambassador Don Bernadino de Mendoza in the hopes that Spain would invade England, and help convert the country back to Catholicism. The details surrounding Ballard’s conversations with Mendoza are hazy, but in May 1586, Ballard would get the news that a strike force of 60,000 Spanish, French, and Italian troops were set to attack England by the end of that summer.

However, this invasion appears to have relied upon Elizabeth’s death, and once the so-called Babington Plot was thwarted, this uprising never took place (Nicholl 149).

Robert Poley (coincidentally present at Marlowe’s death,) Barnard Maude, and Gilbert Gifford (working as a double-agent) were all hired as intelligencers (spies) for Sir Francis Walsingham. It is believed that Poley spied on Babington, Maude spied on Ballard, and Gilbert Gifford had his sights on John Savage.

Meanwhile, Babington was serving Ballard as a messenger, carrying a letter detailing the plot to Mary, Queen of Scots. When the letter was intercepted, Babington was brought to Walsingham. Babington hoped that he would escape a conviction for treason in exchange for information relating to the plan. This is precisely what Walsingham wanted as well – an admission that Queen Mary of Scots was actively conspiring against the throne.

Once Walsingham obtained the letter, Mary denied all involvement.

At first, Babington thought to persuade Walsingham that his intentions were to come clean about the conspiracy later down the line – instead, he headed to St. John’s Woods where he would spend 8 days, filthy and starving, hiding away from officials.

However, as Walsingham only copied a version of the letter, the validity of the document ended up being highly controversial between Mary’s defenders and the government. Mary denied any involvement with any sort of letter, but her secretaries reportedly confirmed that it was her handwriting. With current evidence, we don’t truly know if, and to what extent, the letter was tampered with.

In August of 1586, Ballard, Savage, Tichbourne, and Tilney were arrested for high treason.

On September 13, 1586, Ballard, who could barely walk due to intensive interrogations, Savage, Salisbury, Babington, Tichbourne, Barnwell, and Dunne were charged with high treason and sentenced to death two days later.

One should remember that Walsingham was not necessarily overreacting when searching out Catholic plots against his Queen. In 1570, Pope Pius V claimed that Elizabeth was an apostate, and papal bull excommunicated Elizabeth for reforming England back to Protestant roots. The Queen’s 1558 Act of Supremacy declared the Church of England’s independence from Rome and the 1559 Act of Uniformity restored the 1552 Book of Common Prayer back into common practice. (Bennett and Jeromski)

The first day of execution had been horrifically gruesome – Elizabeth even commented that the executioners needed to act more dignified during the next execution session, as the executioners had mutilated, and disemboweled most of the conspirators.

Elizabeth dealt with a great deal of emotional turmoil pondering what should be done with her cousin, as she lived most of her life believing Mary would never commit such an atrocity. She laters rationalized the execution of Queen Mary of Scots with “ne feriare, feri,” suffer or strike; strike in order not to be struck (Loades 233).

Works Cited

Bennett, Kristen Abbott and Andrew Jeromski. “‘The Glory of Our Sexe’: Elizabeth I and Early Modern Women Writers.” Women Writers in Context, Northeastern University, May 2020, wwp.northeastern.edu/context/#bennett.glory.xml.

Rutter, Tom. The Cambridge Introduction to Christopher Marlowe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Nicholl, Charles. The Reckoning: the Murder of Christopher Marlowe. University of Chicago, 1995.

Anthony Babington (1561-1586) was an English conspirator famous for being the leader of a plot to murder Queen Elizabeth, known afterwards as “The Babington Plot.” He was born October of 1561 and secretly raised a Roman Catholic. He went on to Sheffield to serve under Mary Queen of Scots, with whom he developed a close relationship. While remaining close to Mary, he and his father, John Ballard, led an April 1586 plot to Murder Queen Elizabeth to start a Catholic uprising against England and liberate Mary. Robert Poley and Nicholas Skeres, known for the murder of Christopher Marlowe, were described as “chief actors” in the Babington Plot. Later, letters were intercepted by Sir Thomas Walsingham; Babington was caught and convicted of treason. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London for about a month before being executed in Lincoln’s Inn Fields on September 19th, 1586. As some scholars note, the Babington plot had much influence on Marlowe’s writing of Tamburlaine, one of Marlowe’s most famous plays.

Despite scarce information surrounding Richard Baines’ early life, he graduated from Cambridge University in 1576 and became an Elizabethan intelligencer. Given his profession, he most likely frequented the Tower of London and reported to Sir Francis Walsingham. Starting in 1579, he spent four years of his life at the English College at Rheims in France. While at the seminary he became a deacon, and eventually a priest. After plotting to poison the seminary’s well, he was imprisoned for one year. Evidence suggests that Marlowe was also in Rheims at this time doing similar intelligence work. Baines is most well-known for his memorandum regarding Kit Marlowe. Baines scornfully described the playwright, specifically attacking Marlowe’s religious beliefs as atheistic. This caused intrigue, as his note was delivered to Crown authorities just before Marlowe’s death in 1593. There are many questions regarding whether or not Baines’ himself played a role in Kit’s demise.

William Bradley (c. 1563-1589) was the son of William Bradley, Sr. and was raised on the corner of High Holborn and Gray’s Inn Lane. Bradley was frequently in trouble; his most famous fight involved Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Watson on Hog Lane in the fall of 1589. There are many conjectures about how this came about. A likely version is that Watson was collecting a debt from Bradley on behalf of innkeeper John Alleyn (brother of Edward “Ned” Alleyn) and made Bradley angry. On September 18, 1589, Bradley was walking down Hog Lane looking for Watson, but was confronted by Marlowe instead. Bradley and Marlowe drew swords; Watson appeared shortly after. Bradley struck first, stabbing Watson, but Bradley was no match for the other two men. Watson stabbed Bradley in the heart, killing him instantly. Bradley’s known associates include Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Watson, Hugo Swift, and John Allen.

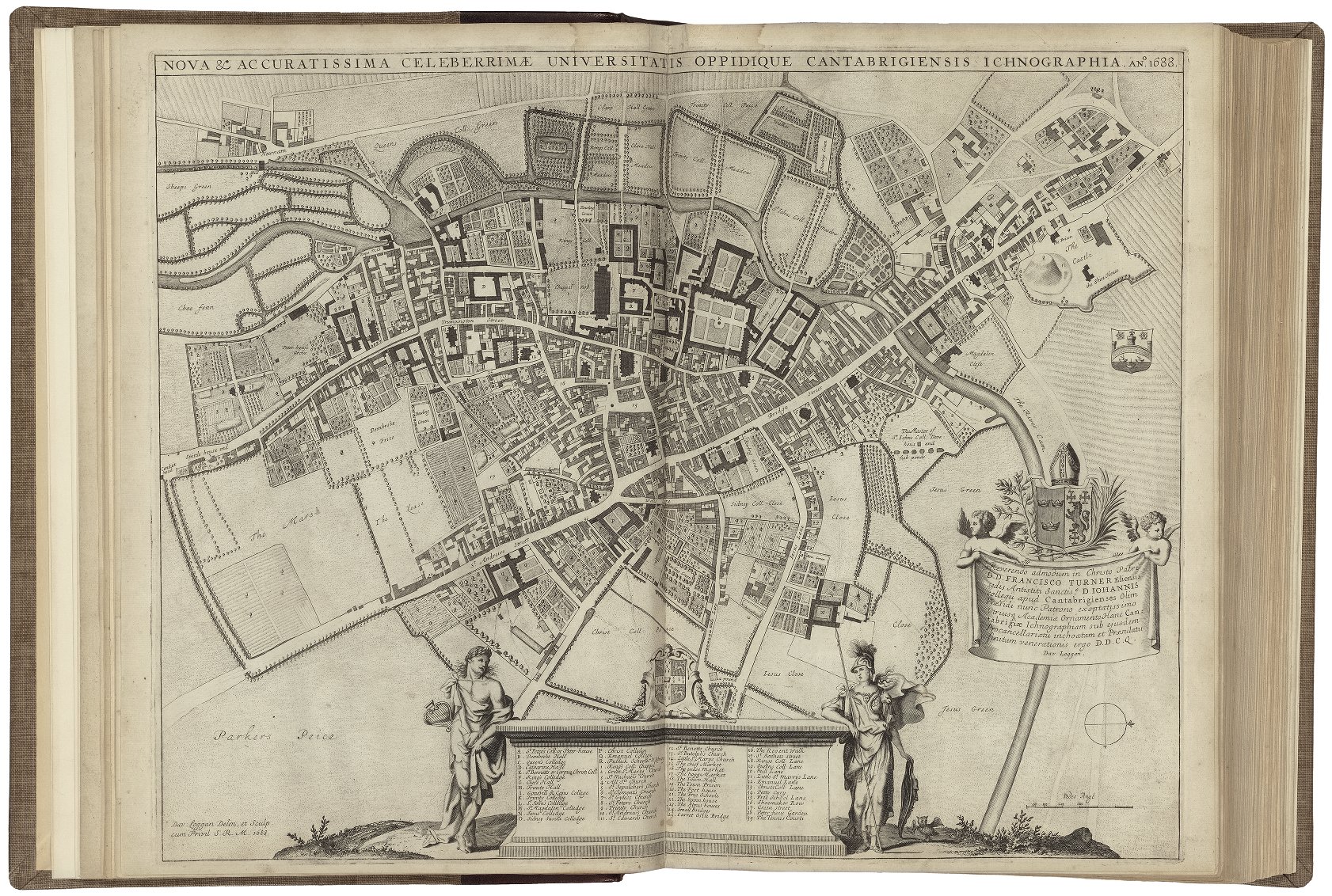

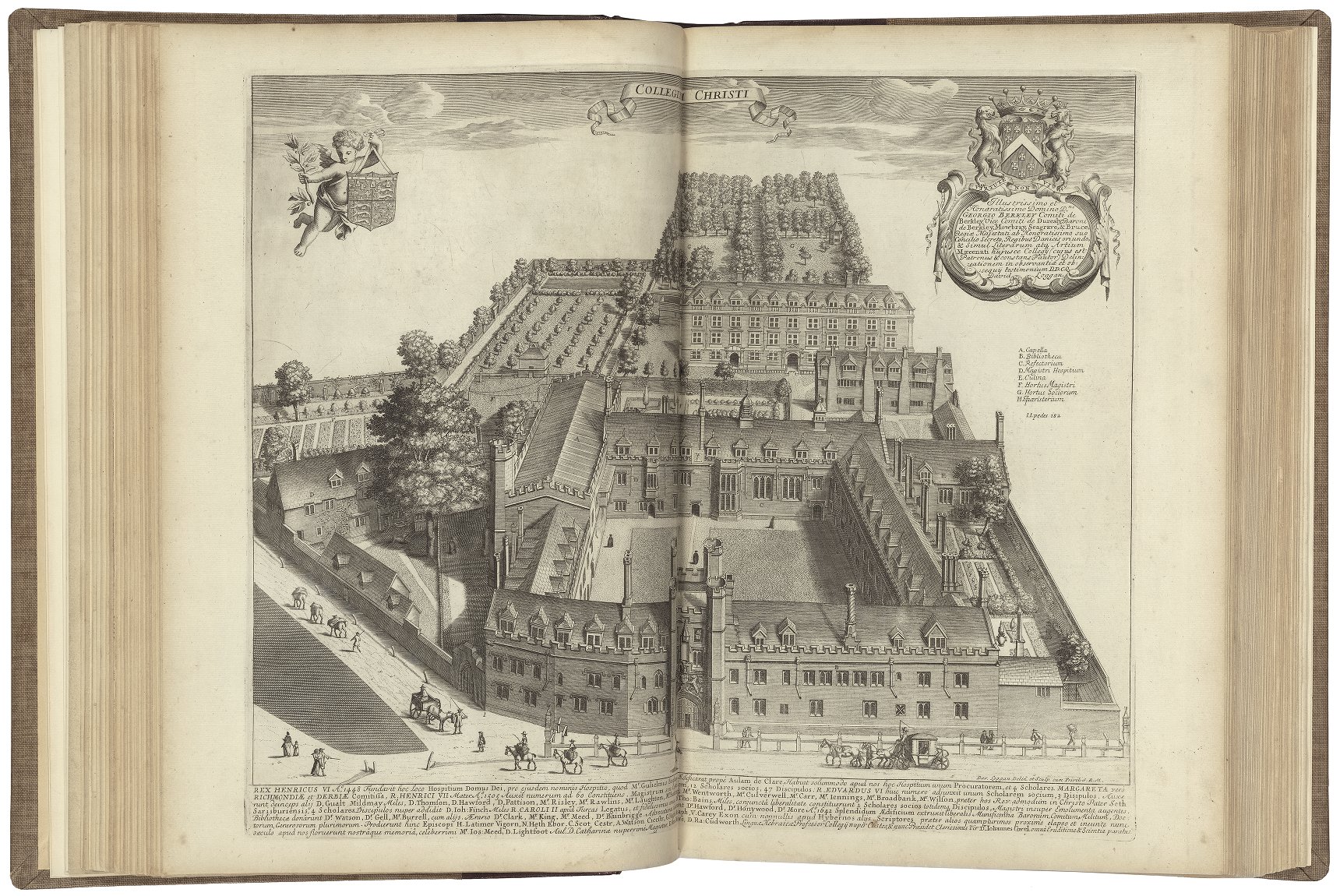

Nestled next to the River Cam, the Cambridge University of medieval England was a completely different institution than today. In its earliest days, the University had no private premises; it used community churches such as Great St. Mary’s and St. Benedict’s as sites for public ceremonies. Lodgings were located on private property, where students were frequently pushed out by landlords or abandoned.

During the late fourteenth century, the University was endowed with property and began construction on a group of buildings called the “Schools,” surviving today as the “Old Schools.” The first School to be finished was the Divinity School, where lectures on religious instruction were held. The Divinity School also housed the University’s chapel, library, and treasury.

In the thirteenth century, most surrounding private land was acquired by the University, allowing new institutions called “Colleges” to be established. These Colleges were originally only allowed to be for the use of Law or Divinity students. Eventually, the Colleges opened their doors to undergraduates of different areas of study.

The earliest College was St. Peter’s (or Peterhouse), founded in 1284. In the following one hundred years, the Colleges of Michaelhouse, Clare, Pembroke, Gonville Hall, Trinity Hall, Corpus Christi, King’s, Queen’s, and St. Catharine’s were built. The Colleges began to dominate the culture of the University and a number of scholars were attracted to its culture, including Erasmus of Rotterdam. His innovations helped steer the University away from pure theological study to a more philosophically speculative course of education.

Following the English Reformation, Cambridge was a hotbed of religious controversy. Its Colleges each had their own culture and religious leanings; there were Catholic/Protestant tensions, as well as Protestant schisms.

Cambridge was home to controversial public figures, including William Perkins, an extreme Calvinist preacher who earned his Bachelor’s in 1581, and was elected a fellow of Christ’s College in 1584. He was famous for his Puritanical sermons, and his success at the University stoked anti-Calvinist sentiment across the country.

This site’s central figure, Christopher Marlowe, attended Cambridge on a “poor boy’s” scholarship, entering Corpus Christi College in December 1580. Although Marlowe’s personal religious views remain ambiguous, no doubt he was exposed to much of the religious debate at the University. Marlowe earned his Bachelor’s in 1584, and after a leave of absence submitted his application for his graduate degree in 1587. It is unclear what Marlowe was up to during his leave of absence, but there is speculation he worked as a Spy for the Queen’s Privy Council in France during these years.

Marlowe returned to Cambridge but he was not received warmly. He was charged by his College on counts of disorderly conduct, and more seriously on charges grounded in suspicions that he left “Cambridge for the University of Douai for good.” The University of Douai was a Catholic institution and the center of many plots against Queen Elizabeth. Marlowe presented a letter of amnesty from the Privy Council, and the University grudgingly obliged him with a graduate degree.

Today the University of Cambridge is home to 31 colleges yet retains its medieval feel in the architecture of the old colleges and parts of the town.

George Carey, 2nd Baron Hunsdon (1547- Sept. 9, 1602) was the second cousin of Queen Elizabeth I, Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household, and a patron of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men for Shakespeare.

George Carey was the oldest son of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon and Anne Morgan. In 1560, George Carey entered Trinity College, Cambridge and later continued to have a successful military career, fighting in the Northern Rebellion in 1569. Carey was knighted for his bravery by the Earl of Sussex. Later, Carey moved into politics and became a member of Parliament for the county of Hertfordshire (1571) and for the county of Hampshire (1584, 1586, 1589, and 1593). In 1597, he was appointed Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household, following in his father’s footsteps. As Lord Chamberlain, he was a patron of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the theater company of actors for Richard Burbage and William Shakespeare. That same year, George was invested as a Knight of the Garter, a prestigious event that is said to be the first performance of Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor and one in which Christopher Marlowe may have also taken part.

Henry Chettle is a well-known Elizabethan printer and playwright connected with many high-profile writers including William Shakespeare, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Nashe, Anthony Munday, and Thomas Heywood. Chettle established himself as a great collaborator, working with many authors and contributing to many famous plays.

In 1577 his father, Robert Chettle, apprenticed him to learn the trade of printing in London. Over the course of his life, Chettle worked with over 48 plays in the 1590s and early 1600s. Of those 48 plays, Chettle is said to have written 12 of them entirely by himself, while partially editing or contributing to the rest. Some significant plays that Chettle worked with were: Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit, Romeo and Juliet, Patient Grissel, The Tragedy of Hoffman: or a Revenge for a Father, The Blind Beggar of Bethnal, and Sir Thomas More.

One of Chettle’s most noteworthy contributions was to the play Sir Thomas More. The play dramatizes the former Lord Chancellor of England’s execution after he refuses to support Henry VIII’s separation from the Roman church. The authorship of this play is unclear, however, many believe it to have been first drafted by Anthony Munday. Scholars believe that Henry Chettle assisted in the 1590s, and that contributions from Thomas Dekker, William Shakespeare, and Thomas Heywood followed. This play exists in one singular manuscript, in which scholars have analyzed handwriting styles to identify who made which contributions. Hand “D” has been identified as Shakespeare, whereas most believe Chettle to be “Hand A.” The play was never printed and there is no record that it has ever been acted out on a stage.

Despite his work with many well-known and significant plays, much controversy surrounds Chettle’s work, relationships, and overall authenticity. In 1591, Chettle entered a partnership with the notorious printers William Hoskins and John Danter. Hoskins and Danter were responsible for printing the 1597 “bad” quarto of Romeo and Juliet, and Chettle reputedly contributed to the work’s inconsistencies. The quarto has been labeled “bad” because the writing is unlike Shakespeare’s. One theory is that the quarto’s source was an “actor-reporter” who improvised lines, another is that Chettle is a bad editor.

The year 1592 is the first time that there is solid evidence of Chettle’s writing career taking off. However, the details of Chettle’s career remain mostly unknown due to a lack of evidence. For example, Chettle helped publish a pamphlet called Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit, yet some like Shakespeare and Marlowe believed that Chettle authored the work. In Kind Hearts Dreame, which Chettle published under his ow name, he shut down such claims that he authored Greene’s Groatsworth. Despite his denials, there is contradictory evidence and uncertainty remains.

In the face of ambiguity concerning the details of Chettle’s life and career, Philip Henslowe’s diary offers some clarity. Henslowe’s diary documents multipl loans made to Chettle, suggesting that Chettle may have been on the brink of poverty, or over it. In 1599, one of these loans was made to help Chettle gain release from Marshalsea prison. The date of Chettle’s death is uncertain, but he certainly left a mark, however blurry at times, as a printer, writer, and dramatic collaborator.

Samuel Daniel (1562-1619) was an English poet, historian, and playwright. Daniel’s known associates included William Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser, and Sir Walter Raleigh. Born in 1562, he studied at Oxford University. He left after three years to study poetry and philosophy, and became a servant of the English ambassador to France. The Countess of Pembroke, Mary Sidney, encouraged him to write. His first well known work was a 1592 collection of sonnets addressed to “Delia.” He later became a successful court poet, writing both poetry and plays such as, The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses and Philotas. He would remain secluded in his home, located on Old Street in London (near The Curtain Theater) for months at a time seeking inspiration and ideas for his writings, only coming out to socialize with friends. He eventually gave up his benefactors and court titles, effectively ending his writing career. He retired on a farm where he died in 1619.

Thomas Drury (1551-1603) was a government informant who accused Marlowe of atheism.

Drury worked for Sir Nicholas Bacon as a government informant and messenger. Drury attended Caius College, but didn’t earn a degree. He was arrested in 1585 for no documented reason. The length of his stay at the Fleet Prison is unknown. Drury accused Richard Cholmeley of atheism in a letter he called “The Remembrances.” He was tasked with investigating Christopher Marlowe on charges of atheism and blasphemy in regards to the Baines Note. Supposedly, the Elizabethan government commissioned Drury to publicly accuse Marlowe of atheism. Less than one month later, Marlowe was killed. Unable to stay away from trouble, Drury was in prison several times.

Francis, the Duke of Anjou and Alençon, son of France’s King Henry II and Catherine de Medici was born under the name ‘Hercule’ in 1555. As a child he suffered from various ailments, spinal issues, and the loss of his older brother, Francis II. Hercule then adopted ‘Francis’ as his own Christian name.

In 1570, another of his brothers, King Henry III of France, sought peace-keeping measures amidst Europe’s increasing religious tension. Catherine de Medici, who openly opposed the protestant practices, is credited with ordering the Huguenot massacre in Paris. The violence spread to surrounding cities like: Orléans, Bordeaux, Troyes, and countless more. The Huguenot population subsequently plummeted from death and conversion out of fear. Francis allegedly incited massacres outside of Paris on his own accord, without the king’s blessing. This widespread ambush on the Huguenots catalyzed a fourth religious war in France, only ending with Henry IV’s coronation in 1598.

After Henry III signed the “Edict of Beaulieu,” in 1576, Francis became the Duke of various French lands; most significantly, Anjou. Soon after, England’s Queen Elizabeth showed interest in potentially marrying Francis, now a Duke. This union was only given serious thought in the late 1570s, when both France and England sought to retain control over Europe’s unstable religious and political atmosphere. The two were known to be mutually flirtatious despite their age difference of roughly twenty-two years. She is stated to have playfully dubbed him as her ‘frog’, a not-so-positive term ascribed to French people. Francis was among few of the many foreign suitors to actually meet with Elizabeth in person. Via documented love-letters and poems, a mutual love affair seems to be at the least staged. Her last letter to him titled, “On Monsieur’s Departure,” is predominantly viewed as her reflection of what could have been, but some theories point to underlying allusions to other love affairs she was possibly engaged in. The plan is believed to have been superficial with no real intentions on either side.

Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s secretary, served as liaison for the marriage. France wanted the marriage before an armistice whereas England sought a treaty preceding the marriage, therefore Walsingham had little success. The Treaty of Plessis-les-Tours in 1580 between the Dutch States General–with the exceptions of Zeeland and Holland–and Anjou, saw Francis assume nominal sovereignty over the Dutch Republic and become the “Protector of the Liberty of the Netherlands.” He was unable to make his initial appearance in his new territories until 1582. The Dutch did not uniformly receive their new “protector” well. Francis used the custom of the Joyous Entry, where a monarch peacefully visits a newly acquired land, as a ruse to bring resistant cities under his control by force. As he approached the city of Antwerp, the people were not fooled and anticipated an attack.

The Duke of Anjou then grew famous for the French Fury, where he was thoroughly defeated in his effort to lay siege on Antwerp. This insulting defeat was soon followed by scolds from his family members along with the official redaction of Queen Elizabeth’s engagement; A popular decision among her councilmen and country-folk. In 1584 malaria infected the young Francis, he died in Paris at twenty-nine years old. His death sparked further religious violence in Europe as the new heir to the French throne became Henry the Great of Navarre, a Protestant. He became Henry IV, ruling over France with unprecedented religious tolerance, only to be assassinated in 1610 by a radical Catholic.

Robert Greene (1558-1592) was a popular English pamphleteer and dramatist. He was baptized in Norwich on July 11th, 1558. Greene matriculated as a sizar at St. John’s, Cambridge where he received his BA. Later, he received his MA at Clare College, Cambridge. Upon graduation, Greene married and embarked on his literary career; he soon abandoned his wife and newborn child. He is known as one of the “University Wits,” a group that includes George Peele, Thomas Nashe, Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Kyd, John Lyly, and Thomas Lodge. Greene is best known now for a pamphlet he may or may not have had a hand in, Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit in which the author implies that Shakespeare is an “upstart crow.” He died on September 3rd from (according to Gabriel Harvey) a surfeit of pickled herrings and Rhenish wine. He would have died in the streets if it wasn’t for the care of a Dowgate shoemaker.

Thomas Harriot (1560-1621) was an English scientist who made terrific advances in various branches of mathematics such as astronomy and navigation. He studied at Cambridge and is reputed to be the first person to look at an astronomical body through a telescope in 1609. Harriot was close to Sir Walter Raleigh and together they traveled to the New World where they made advances in navigation, cartography, and anthropology. Harriot and Raleigh were also friends with Christopher Marlowe, who was reputed to share their interest in the “alien” and the “exotic,” and were believed to comprise part of “The School of Night,” a group of intellectuals who debated occult topics. Harriot achieved many remarkable feats including writing the first book in English about visiting America and discovering Snell’s law of refraction before Snell himself did (see Galileo Project).

Gabriel Harvey (1550-1630) served as a Praelector and professor of Rhetoric at Cambridge University from 1574 to 1576 – he graduated from Christ’s College, Cambridge in 1570.

Born in Saffron Walden, Essex, Gabriel was the eldest son of John and Alice Harvey – a farmer and rope maker.

Gabriel’s brothers, Richard and John become entangled in a literary feud against Thomas Nashe. While John never wrote publicly on the issue, Richard would defend himself in the preface of The Lamb of God and his enemies, (1590) only to be mocked by Nashe in return.

Harvey was committed to relaying his perspective on contemporary literary history with his detailed marginalia (notes scrawled into the margins of books) on the works of writers such as William Shakespeare, Robert Greene, Francis Bacon, Henry Butt, and George Gascoigne.

![Manuscript marginalia: Gabriel Harvey refers to Hamlet and Richard III

Creator: Gabriel Harvey

Title: Annotations by Gabriel Harvey in Facetie, motti, et burle di diversi signori et persone private and Detti, et fatti piacevoli et gravi, di diversi principi filosofi, et cortigiani [manuscript], ca. 1580-1608?

Date: ca. 1580-1608?

Repository: Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, USA

Call number and opening: H.a.2, sigs. 161v-162r](https://kitmarlowe.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/screenshot-37.png)

Harvey’s obsessive note taking habits may have been mocked by his Cambridge peers, but his process of rereading material in order to replicate and evolve prose is exhibited in his later works. Harvey’s studying habits are best described by himself in the marginalia of Petrus (Peter) Ramus’s Ciceronianus, in which he writes “I redd ouer this Ciceronianus twise in twoo dayes, being then sophister in Chistes College” (172 Wilson).

Harvey’s first publication, Ode Natalia, (1575) is an elegy dedicated to Petrus Ramus, a French philosopher whose rhetorical method and theories on educational reform greatly influenced Harvey’s career. Harvey also published two Latin translated orations focused on this issue – The Rhetor (November of 1577) and Ramus’ Ciceronianus (June 1577).

The Rhetor debuted in 1575 at Trinity College, Cambridge as a speech about how rhetoric should be used and its future. Ciceronianus was also given as an oration in the spring of 1576, but is more focused on how one should teach these forms of rhetoric.

Cicero had a great influence on Harvey’s life from a young age. Harvey writes in his introduction to Ciceronianus, ““Long since I laid claim to the name of a Ciceronian [He writes], and considered this title the highest honor and glory. I firmly agree with those who taught that Marcus Tully alone should be imitated, forever and everywhere; and who believed that in him reposed the fortunes of eloquence and letters.”

On July 27th of 1578, Harvey made an address to the Queen (and was possibly in charge of welcoming her to Audley End, although Harvey’s adversary Thomas Nashe refutes this in his piece, Have with you to Saffron Walden (1596)). In his address, he presents the Queen with the manuscript for his forthcoming book, G. Harveii Gratulationum Valdinensium Libri quatuor (Gratulationum Valdinensium four Books). Each part of the collection is dedicated to a different person, or group including Queen Elizabeth, The Leicesters, Lord Burghley, and finally, a criticism of Oxford.

In 1581, Trinity College performed Pedantius, a comedy in which the main character was an obvious caricature of Harvey – even going to the extent of making the main character a Cicereon schoolmaster. Of course, Thomas Nashe found the play hysterically, calling it an “exquisite comedy” in Have With You to Saffron Walden (1596).

At the turn of the 1590’s, Gabriel’s brother Richard Harvey had taken part in the Marprelate controversy with his preface to The Lamb of God and his enemies. In response, Robert Greene decided to personally satirize each member of the Harvey family in his piece A Quip for An Upstart Courtier). Thomas Nashe, directly attacked in Lamb of God, would also rebuke Richard in a passage from his respective work, Pierce Penilesse His Supplication to the Divel (1592). Gabriel would go on to respond to both Nashe and Greene in Foure Letters (1593).

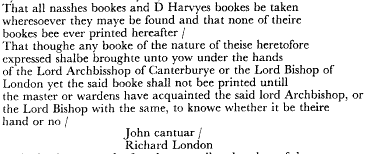

The never-ending counter attacks on each side was ultimately halted by Bishops’ Ban on satire in 1599 – Thomas Nashe and Gabriel Harvey were both banned from writing any more future novels.

Harvey died of unknown causes in 1630; he is buried at Walden Abbey in Saffron-Walden.

Born in either 1555 or 1556, Anne Hathaway, also recorded as Agnes, was the eldest of her eight siblings. She lived on a farm formerly known as Hewlands, but now is called Anne Hathaway’s Cottage. Hewlands functioned as a sheep and crop farm. When her father Richard Hathaway passed away, he left Anne six pounds, thirteen shillings, and four pence to be given to her on her wedding day.

Controversially, Hathaway married William Shakespeare in November of 1582, just months after becoming pregnant with Shakespeare’s child. Because Shakespeare was younger than Hathaway, and was considered a minor at the age of 18, the couple was granted a special license to marry. Two different variations of Hathaway’s name are found on their marriage documents because of the controversy: “Anna Whateley of Temple Grafton” and “Anne Hathwey of Stratford.”

Hathaway and Shakespeare most likely lived in Henley Street, Stratford-upon-Avon until Shakespeare bought New Place in 1597. Hathaway’s role as Shakespeare’s wife, besides taking care of their children Susanna, Judith, and Hamnet, most likely consisted of baking bread, brewing ale, and tending to the house. However, Hamnet, Judith’s twin and their only son, passed away in 1596 at the age of 11. Some argue Hamnet lives on through Shakespeare’s character Hamlet.

When Shakespeare was away in London, which was often, Anne rented rooms in their home New Place to lodgers, friends, and guests. New Place had two barns, multiple gardens, and two apple orchards. Actor Thomas Greene was also said to have stayed at New Place for quite some time. This created quite a bit of revenue for the family and gave Anne an even bigger leadership role in the family.

Hathaway became a widow at the age of 60 and is mentioned in Shakespeare’s will. Although she had no part in the creation of the will, he left her his second best bed and his furniture. Some think that because it is only the second best bed, the couple maybe didn’t really love each other that much. Others think that this has little significance, for they must have had an agreement before Shakespeare passed that made sure Hathaway would be secure.

The name “Anne” is mentioned only 82 times throughout her husband’s works. However, Sonnet 145 seems to resemble Hathaway the most, as some argue that it is an early love poem for Hathaway. In this sonnet, Shakespeare plays with the combinations of words, “hate away,” which may resemble Hathaway and the throwing away of negative emotions, as well as the throwing away of Hathaway’s maiden name. Also, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, some see resemblances between Hathaway and the character Gertrude, as there was high suspicion that Anne committed adultery with his younger brother.

Hathaway passed away in 1623, in Stratford.

Philip Henslowe was the owner of a few prominent playhouses and a financial keeper for some of the best acting companies in England. He was born in 1550 in Linfield, Sussex, and died on January 6, 1616 in London. Henslowe was also well known for his diary, which holds a record of almost all of the major plays that were performed in this era. It also provided significant information that historians used to discover the chronological geographies of theatrical and non-theatrical business endeavors during the Elizabethan era. In 1587, Henslowe built the Rose Theatre in Bankside, London, which was a dual-purpose venue for Bear Baiting and plays. It was the first public theater in the area that played the tragedies of Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Kyd. Henslowe also built and managed The Hope Theatre. Henslowe was one of the most successful entrepreneurs in the Elizabethan Era. He was responsible for pawnbroking and finances for all his venues. Some described Henslowe as illiterate, moneyed, old, or fraudulent, but there is no doubt that he was a businessman first.

Thomas Kyd (1558-1594) was an influential Elizabethan playwright whose most famous plays include The Spanish Tragedy and The Tragedy of Soliman and Perseda. His parents were Anna and Francis Kyd; he was baptized at Saint Mary Woolnoth church in London on November 6, 1558. His father was a member of London’s Company of Scriveners. Kyd may have been a scrivener for some time, but there is little extant evidence. In 1565, he enrolled in Merchant Taylor’s School in London, a school for sons of middle class citizens. From 1587-1593 Kyd might have been a private secretary at the Queen’s Company of Players.

Kyd shared rooms with fellow playwright Christopher Marlowe. When Crown authorities searched their rooms for evidence of Marlowe’s reputed atheism, Kyd was arrested and tortured. He never fully recovered and died penniless at the age of 35. He was buried in St Mary Colechurch in 1594.

John Lyly (c. 1553/1554 – 1606) was an Elizabethan prose writer, dramatist, poet, and courtier.

Lyly attended King’s School in Canterbury, and Magdalen College at Oxford, earning his BA and MA. The first play he ever published was the prose romance, Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1578). In 1580, Lyly received control over the Blackfriars Theater. His plays were performed by the Children of Paul’s in the presence of Queen Elizabeth. Lyly served as a member of Parliament for three separate municipalities between 1580-1601. He served on a committee about the wine abuse reformation in 1598. In November of 1606, Lyly passed away from disease and was buried at the St. Bartholomew the Less Churchyard.

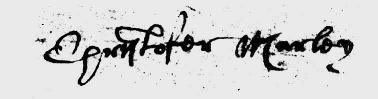

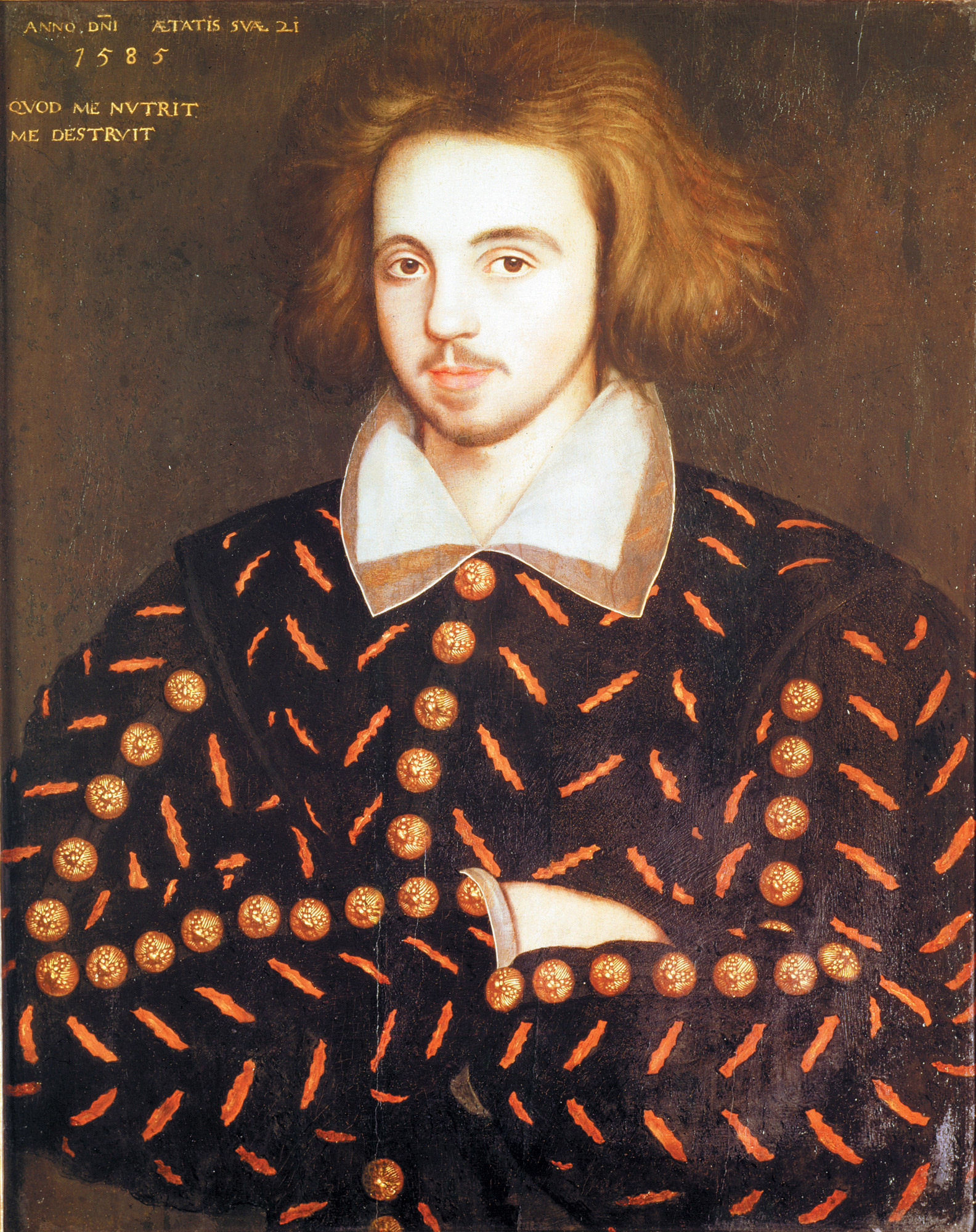

Christopher Marlowe (Christened 1564 – Died 30 May 1593), known to friends by his nickname Kit, was an English playwright and poet who lived a short life ridden with scandal and brilliance. Marlowe was the eldest son of a local cobbler in Canterbury named John Marlowe (see Family Tree). Though his birth is not documented, his baptism in Canterbury was recorded on February 26 1564, just a few months prior to fellow playwright William Shakespeare.

Marlowe’s earliest known education was in 1578 when he earned a position at King’s School in Canterbury. Here, Marlowe became well-versed in Latin classics. In 1580, Marlowe received a scholarship from the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker, to study at Corpus Christi College in Cambridge. This scholarship was offered to those that showed potential in rhetoric and dialect. “Marlowe had to master that language’s complex rules of versification. Classical Latin poetry is metrical, not rhymed: the lines of Virgil’s Aeneid or Ovid’s Metamorphoses are structured not by a rhyme-scheme, but by the need to conform to set patterns of long and short vowel sounds” (Rutter 3).

Blank verse is any line that doesn’t rhyme in the same meter, usually in iambic pentameter. This brought a sort of liveliness in Marlowe’s playwriting that Ben Jonson would later call “Marlowe’s mighty line” in his elegy for Shakespeare.

At Cambridge, Marlowe would study the classical trivium, grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric, as well as philosophy; all course work was conducted in Latin. Students demonstrated their learning in public debates with peers, some of whom may have been Thomas Nashe and Robert Greene, who were then at St. John’s College. It is also likely that Marlowe translated Ovid’s The Amores (first written c. 16 B.C.) at Cambridge, and he and Nashe may also have collaborated on Dido, Queen of Carthage.

Marlowe’s time at Cambridge was notoriously full of gaps, and he nearly didn’t graduate. Many believe these absences support arguments that Marlowe was a spy working for the Elizabethan government. It is believed that during his time at university, Marlowe would have observed his peers for any signs of heresy against the church.

In 1587, authorities at the university attempted to deny Marlowe of his MA due to him not completing his coursework. Officials from the Privy council overruled the decision, suggesting that he had helped the queen herself – another reason why some believe Marlowe to be a spy (See also: Marlowe & Espionage).

Marlowe dealt with constant legal trouble during his life. In 1588, he was sued by James Wheatly for a dispute over a horse, and his Cambridge peer Edward Elwyn sued him for failing to pay back a loan (Mateer). Marlowe also had a reputation for violence. In 1589, Marlowe and fellow poet, Thomas Watson, got into a sword-fight with William Bradley in Hog Lane. Bradley was stabbed to death, by whom is not certain, and both were subsequently jailed at Newgate Prison. Marlowe was released on bail twelve days later, but Watson served for months (accused of manslaughter, released Feb 1590).

Whether he was working for the Anglicans, the Catholics, or both, Marlowe was reputedly skeptical about religion. His first big hit, Tamburlaine, was hardly a celebration of Christian values.

The first known mention of the play Tamburlaine the Great (1587) was in a letter dating 1587, although it was referencing the second part of the play, was apparently written within the same year. While a definitive date for the first showing is unknown, the timeline suggests that Marlowe may have written some of this play while at university.

The play was a massive success and set the foundation for the early modern stage. Throughout the play, signs of Marlowe’s atheism become more apparent as he creates a character that seems to take on God himself. Tamburlaine’s character is one that defies fate and creates his own destiny.

Throughout his short life, Marlowe also wrote Dido Queen of Carthage, Tamburlaine the Great, Part 2, Massacre of Paris, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, The Troublesome Raigne and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second, and The Jew of Malta.

Since the 18th Century, readers of English playwrights have speculated that Marlowe helped William Shakespeare with the conception of King Henry VI. The two playwrights would have been popular around the same time,1590-93, and both of their plays were even shown at the public theater, The Rose. The two were also way ahead of other playwrights at the time in terms of their grasp of blank verse. Recent stylometric studies have confirmed that Marlowe and Shakespeare both contributed to several of these plays, and offer evidence for the collaborative nature of playmaking in early modern London (see “Authorship, DRAFT”).

In the Spring of 1593, a xenophobic poem ordering protestants to leave England was posted on Churchyards around London, and signed “Tamburlaine.” The Privy Council were upset at the libel being spread across the city. While his involvement was unclear, the religious tension Marlowe’s plays created prompted the Privy council to get involved. Marlowe’s flatmate and fellow dramatist Thomas Kyd was allegedly tortured in order to get a confession that Marlowe was an atheist. This led to a warrant being put out for Marlowe’s arrest.

On May 30th, 1593, Marlowe was stabbed to death at Eleanor Bull’s rooming house in Deptford. Was he stabbed by a fellow spy? Was it an argument over the bill, or “reckoning”? The mystery remains.

John Milton, born in 1608, was an English writer of great renown. Known for his prose and his poetry, Milton’s writing offered a re-presentation and critique of political, social, religious, educational, and historical issues. He encouraged readers to parse out meaning for themselves, and offered his text as an opportunity to engage with this process. Recently, scholars have identified Milton’s handwritten notes engaging in William Shakespeare’s plays, making suggestions for editorial emendations; Milton also may have transcribed Shakespeare’s works, offering a new lens through which Milton’s readers might reconsider his own writing. Some of Milton’s most notable works include Lycidias, Comus, Areopagitica, as well as Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained.

Throughout his works, Milton proposes a reformation of church government, including the elimination of bishops, equating the church government to monarchs and tyrants. For Milton, a tyrant is someone who holds themselves above the law. Milton finds that, though man is born free, Adam’s transgression gave birth to governance of man to keep him in check; that being said, for one man to rule over another seems ludicrous to Milton. He believes instead in social contracts and the power of people to overthrow their governing authorities.

Milton’s first decisive critique of church government is seen in Lycidias, an anti-episcopal work. While Lycidias reads as a pastoral elegy, it is notable for its blending of Christian and Pagan imagery, as well as its nascent attempts to “justify God’s ways to man” that we see later in Paradise Lost. In this later poem, readers are seduced by the intense pagan imagery before being redirected toward recognizing how Christian morals and values are superior.

Milton prided himself on his classical education, but also read contemporaries including William Shakespeare and Edmund Spenser. In his Areopagitica, he lauds “our sage and serious poet Spenser, whom I dare be known to think a better teacher than (Duns) Scotus or (Thomas) Aquinas.” Milton considers Spenser’s enchantment of the senses to have conceptual power and finds The Fairie Queene’s world an intellectually fascinating space.

In Milton’s Paradise Lost, one finds echoes of Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus, namely in the representations of hell through Mephistopheles and Satan. For Milton, hell is wherever the Satan goes, and for Marlowe hell is everywhere that Mephistopheles goes — an absence of God. However, Paradise Lost takes a step beyond Faustus and presents Satan in direct opposition to God, who plays a more active role in this later poem.

John Milton’s work is not limited to exploration of Christian stories, though his work provided a fresh take on how those stories could be reinvented through the lens of Greek mythology. His melding of Pagan and Christian imagery presented critique of Christian institutions without deliberately criticizing these institutions. Instead, his writing allows the reader to arrive at their own conclusions as navigated by his text.

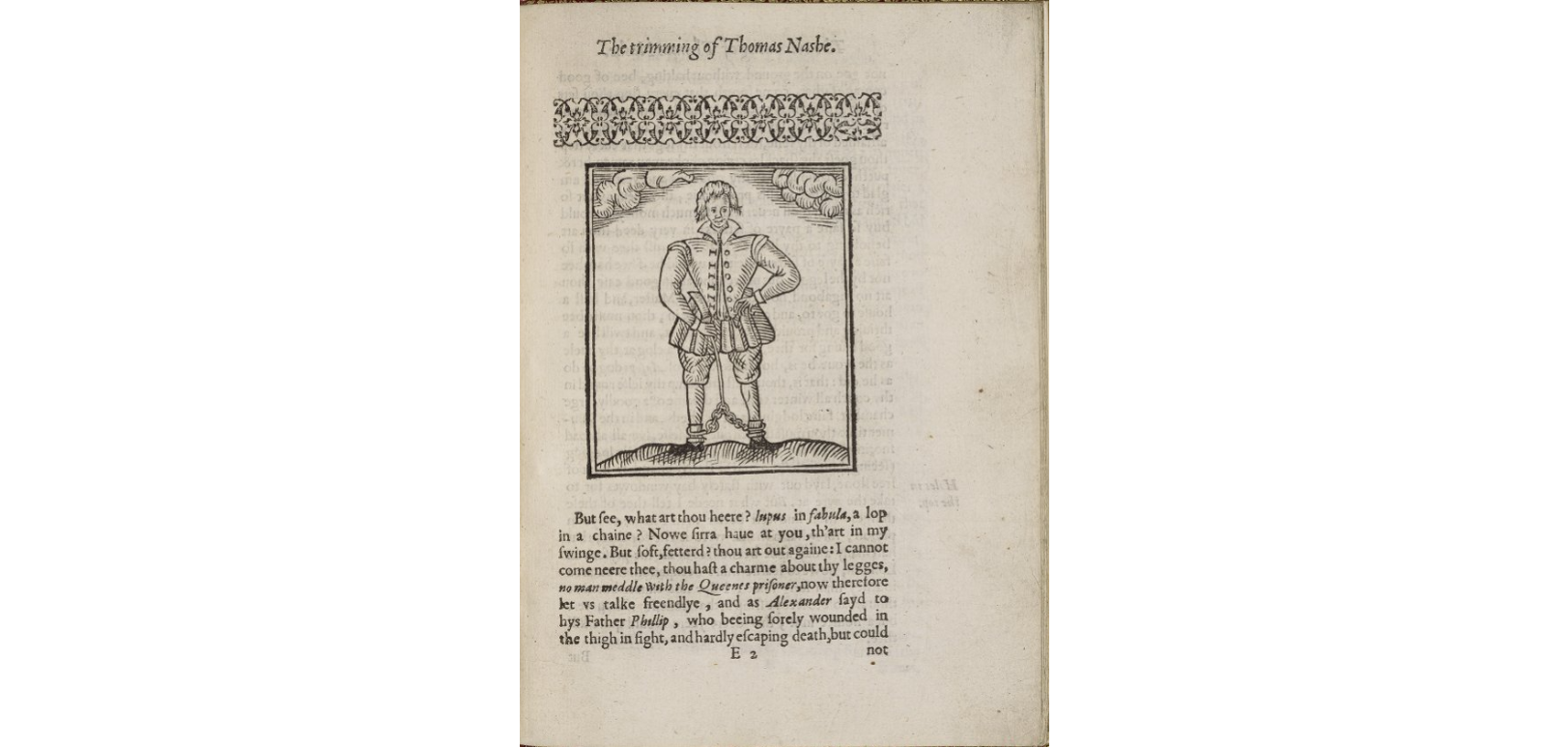

Thomas Nashe (1567-1600/1) was a satirical Elizabethan writer of poetry, pamphlets, and dramatic works. Nashe joined St. John’s College of Cambridge University at 14 and received his BA in 1588.

Nashe’s career would take a turn when the established church was criticized by a Puritan writer under the pseudonym Martin Marprelate. Nashe, along with Robert Greene and John Lyly, were hired by Archbishop Whitgift to dismiss the Puritan propaganda.

Nashe’s first solo published work was The Anatomie of Absurdity (1589), an essay on the contemporary state of learning and early print culture – and his problems with both. His love of rhetoric is clearly conveyed throughout the essay: “Amongst all the ornaments of arts, rhetoric is to be had in highest reputation, without the which all the rest are naked.”

Nashe found himself in trouble when he added an unauthorized epistle to Sir Phillip Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella (1591). The Countess of Pembroke took swift action to take the edition with Nashe’s prefatory epistle out of circulation, replacing it with one omitting Nashe’s contribution.

In 1592-3, Nashe published Strange Newes in response to Gabriel Harvey’s criticism of him in Foure Letters and Certain Sonnets (1592). The primary reason Nashe likely made such an aggressive reply was due to Harvey’s mean-spirited satire of Robert Greene’s death in Foure Letters.

Nashe writes in Strange Newes “Gabriel, I will bestir me, for all like an ale-house knight thou cravest of justice to do thee reason; as for impudence and calumny, I return them in thy face, that in one book of ten sheets of paper hast published above two hundred lies.”

Nashe appears to have attempted to end their public quarrel in a prefatory epistle to Christ’s Teares Over Jerusalem. But Harvey’s publication of Pierce’s Supererogation, (1593) and New Letter (1593), both insulting Nashe, prompted Nashe to re-issue Christ’s Teares with a fresh assault on Harvey.

Even of Maister Doctor Harvey, I heartily desire the like, whose fame and reputation ‘though through some precedent iniurious provocations, and fervent incitements of young heads’ I rashly assailed: yet now better advised, and of his perfections more confirmedly persuaded, unfainedly I entreat of the whole world, from my pen his worths may receive no impeachment.

In 1597, Richard Litchfield published his pamphlet The Trimming of Thomas Nashe, a close reading of Nashe’s Have With you to Saffron Walden (1596). Litchfield criticized Nashe for his writing style, and for dragging out the quarrel with Harvey.

This literary feud was finally halted in 1599 when the Archbishop of Canterbury banned Nashe and Harvey from printing anymore.

In the same year, Nashe would print what many consider to be one of the earliest examples of an English picaresque novel, The Unfortunate Traveler. This travel narrative featuring Jack Wilton remains Nashe’s most popular work to date.

Nashe was associated with Christopher Marlowe, Robert Greene, and Thomas Watson. In 1589, he wrote the prefaces to Robert Greene’s Menaphon and The Anatomie of Absurdity. Nashe co-wrote the now-lost, and likely seditious, play Isle of Dogs with Ben Johnson, for which he would be exiled. He died of unknown causes in 1600/1601.

Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) was born Elizabeth Tudor on September 7, 1533. She was the first daughter of King Henry VIII and only child of his second wife, Anne Boleyn.

King Henry had her mother executed when Elizabeth was three years old, partly because Anne was unable to give birth to a male heir. Although Elizabeth had replaced her sister Mary, Henry’s daughter with his first wife Katherine of Aragon, as heir to the throne, when Anne was beheaded, she lost primacy in the line of succession. Ultimately, Henry’s son Edward IV would succeed his father, followed by Lady Jane Grey (the nine days’ queen), Mary, and then Elizabeth.

From an early age, Elizabeth received a rigorous education, unlike many women during the time period. At age eleven she translated a poem from French to English. By the time she took the throne, Elizabeth was fluent in Greek, French, Italian, and Latin. She was also well-versed in Math, History, Geography, and Astronomy.

When Mary took the throne, she determined Elizabeth was a threat to her reign. A devout (if arguably fanatic) Catholic, Mary had returned England to the “old faith,” and many subjects wanted the Protestant Elizabeth to rule instead. Mary ordered Elizabeth locked in the Tower of London from 1554 until her own death in 1558.

When she took the throne in 1558, Elizabeth followed her father and returned England to Protestant rule. This created an uproar between the Catholic church and Queen Elizabeth I. The Pope even went as far as to tell the people of England that killing the Queen would not be viewed as a sin.

One of Queen Elizabeth’s greatest accomplishments was defeating the Spanish Armada in 1588. Philip of Spain had attempted to invade England and force them back to Catholicism in the name of the Catholic Church. The Spanish invasion was thwarted by a storm, and England was victorious. This victory brought Queen Elizabeth adoration from her subjects, and a large sense of pride surged throughout the country.

Despite her advisors urging her to marry and produce an heir, Queen Elizabeth I notoriously refused. Instead, she chose to marry her country; England would be her husband and its people her children. She was referred to as “The Virgin Queen.”

Elizabeth’s lack of an heir, however, worried her people, especially as she grew older. Eventually, she named James IV of Scotland as her heir, the second son of Queen Mary of Scots, one of Elizabeth’s enemies who she’d had executed in 1587.

Queen Elizabeth I died on March 24, 1603 after reigning for 45 years.

The words on her tomb in Westminster Abbey read, “Here lyes interr’d Elizabeth, A virgin pure untill her Death.”

Sir Walter Raleigh (1552/1554-1618) was a member of the landed gentry, who also served as a soldier and Captain of the Queen’s Guard. Known for popularizing tobacco in England, Raleigh was also a scholar, poet, musician, courtier, and explorer. He was a successful business man, and served as a member of Parliament.

Raleigh volunteered in the Huguenot army in France and attended Oxford University. He was favored by Queen Elizabeth I, who appointed him a Captain in the Queen’s Guard. In 1584, Queen Elizabeth I granted him a royal charter to colonize in the New World. Raleigh was notorious for his involvement in a group called the “school of night,” which included Thomas Harriot, Christopher Marlowe, and George Chapman. James I, the first Stuart king of England, was convinced that Raleigh was conspiring against his throne and England. Raleigh was arrested in 1603, by English authority and imprisoned for thirteen years, but later released in 1616. He was executed for treason on October 29th, 1618, at the Palace of Westminster.

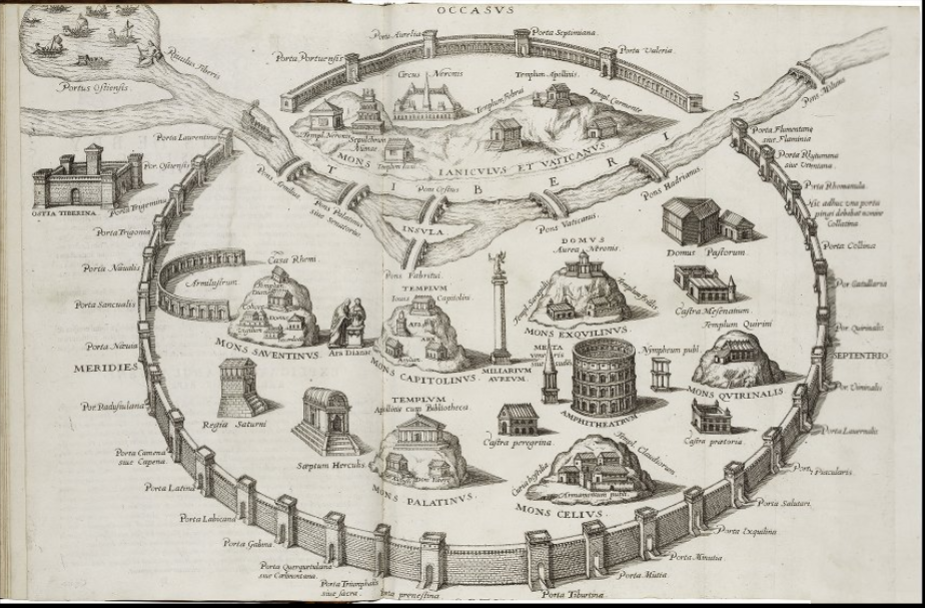

While Queen Elizabeth I ruled England, her person and government gave playwrights, pamphleteers, and others contributing to popular culture much fodder with which to debate the country’s ethics, religion, and politics. Of course, criticizing Queen and country was risky business. Rome emerges as a popular geographical foil for commenting upon the English political landscape, succession, social inequity, and the religious tensions that characterized the Reformation.

Rome was essentially the capital of Catholicism during Elizabeth’s reign. As head of the Anglican (later Protestant) church, Elizabeth was perhaps the most religiously tolerant Tudor ruler, but that was not enough for Catholic Rome. Although Elizabeth permitted Catholics to worship privately (unlike her sister Queen Mary who, when the situation was reversed, brutally killed hundreds of Anglicans earning her the name “Bloody Mary”), they were fined for not attending Anglican services, and punished without trial if suspected of plotting against her. The Tudors ruled under a theory of the divine right of kings (they were chosen by God to rule), but with each change in religion the subjects feared for their salvation after death and began to doubt the Tudor claim to the throne. The split between Anglican and Catholic religions caused Pope Pius V to excommunicate Queen Elizabeth I from the church in 1570. Pius V announced that it was not a mortal sin to kill Queen Elizabeth I, effectively pitting millions of Catholics against her. Plots against Elizabeth escalated from this point forward. Laws surrounding what could and could not be said about her reign became increasingly restricted, and some subjects began to think of her as a tyrant.

Because of the dangers associated with speaking ill of the monarchy, writers often juxtaposed England with Rome in order to avoid punishment while still commenting on topical events. It became a touchstone for political debates, art, politics, and military strategy. Roman mythology offers Elizabethan writers an opportunity to both mythologize their Queen, associating her with Cynthia, Diana, and Astraea, plus Rome offers the distance writers needed to critique the Queen and her court without the risk of punishment.

For example, Shakespeare’s plays Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus, and Titus Andronicus use the ideals of Rome and Romans in order to integrate the use of Roman history in English culture while also interrogating the role of the people under tyrannical rule in conjunction with the monarchy. Although many consider the above to be the “Roman plays,” Shakespeare uses Rome as a foil to criticize English politics, society, and religion in plays Richard III and Henry IV.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616); Although not a “Londoner,” Shakespeare spent most of his working life there, writing and performing plays still well known today, and socializing in the same literary circle as Christopher Marlowe and other University Wits.

After Shakespeare left Stratford-upon-Avon to pursue his professional career, he moved to London around 1590. Residences of Shakespeare in London include Silver Street in Shoreditch (1), as that was where the first playhouses were built, like The Theater and the Curtain (2). Great literary talents Tomas Watson and Christopher Marlowe lived nearby in the Liberty of Norton Folgate, just south of Shoreditch. Robert Greene also lived in the area. George Wilkins – who most likely collaborated with Shakespeare – may also have spent early years there. There is also evidence of Shakespeare residing across the Thames River in the Liberty of the Clink in Southwark, Surrey, (3) due to the opening of the new Globe Theater. The date he retired back to Stratford is unclear, but the burning down of the Globe on July 25, 1613 marks both a symbolic and approximate date for when he stopped coming to London.

Shakespeare has many ties to the “University Wits,” especially through Marlowe. Marlowe dedicated Hero and Leander to Thomas Walsingham, who employed Marlowe as an intelligencer, and this work influenced Shakespeare. Both Shakespeare and Marlowe’s names are mentioned by Robert Greene in his Groats-worth of Wit (1592), with many scholars concluding that Greene’s famous “upstart crow” line was directed at Shakespeare for being an actor with the temerity to write his own plays, despite not being a university-educated playwright. There is much ongoing research and debate about the extent of the literary connection between Marlowe and Shakespeare, but one scholar, Robert A. Logan, in Shakespeare’s Marlowe, cites that about twenty of Shakespeare’s plays have traces of Marlowe’s influence, and eight of the twenty include actual quotations from Marlowe’s works. Logan believes it’s reasonable to think that Shakespeare and Marlowe would have seen each other’s work, as both Henry VI and The Jew of Malta were being performed at the Rose Theatre in 1592. Arguments against Marlowe’s authorship are due to his death in 1593. However, new evidence from the New Oxford Shakespeare credits Marlowe in parts of Henry VI. It is also believed by other literary researchers that Marlowe had a hand in Edward III, because two scenes in the play shadow twelve variables and passages of Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great. Theories and arguments continue to develop as scholars continue to uncover the connection between Shakespeare, Marlowe, and the other University Wits.

______________________________________________________________________________

- *Silver Street in Shoreditch

- *The Theater and the Curtain

- *The Liberty of the Clink, Southwark, Surry

*Found in Nicholl, Charles. The Lodger Shakespeare:

His Life on Silver Street. London, Viking, 2008.

Nicholas Skeres (March 1563 – c.1601) was a con-man and government informant.

Skeres worked as a servant for Thomas Walsingham. He was a government provocateur and a part of discovering the Babington Plot, working as a spy with Francis Walsingham. Skeres was involved in cases of fraud throughout his life, once working with Ingram Frizer. He was sentenced to Bridewell Prison for all of the crimes that he had committed. On May 30, 1593, Skeres and Robert Poley witnessed Ingram Frizer stab Christopher Marlowe at Eleanor Bull’s House over a dispute on the bill.

Richard Topcliffe served Queen Elizabeth as an interrogator in 1557 at the Tower of London and Bridewell Prison. Bridewell is presumed to be where Topcliffe interrogated Thomas Kyd. He was considered a merciless persecutor of Catholics. It is stated that “no blot is more fowl on the history of Elizabeth’s latter years than the name of Richard Topecliffe” (Betten 191). Two of his other victims (among countless others) were Ann Bellamy and Robert Southwell. He was associated with Somerby in Lincolnshire, and Beverly in Yorkshire (Walsh). Topcliffe died December 1604 in Derbyshire.

Francis Walsingham (1532-1590) was Queen Elizabeth I’s principal secretary and spymaster.

He attended King’s College in Cambridge and continued his studies in France and Italy. As a Member of Parliament for Lyme Regis, Dorset, Walsingham worked with William Cecil and Lord Burghley spying on suspicious foreigners in London. Christopher Marlowe may have worked with Walsingham as an intelligencer. After the St. Bartholemew Massacre, he became Secretary of England in 1573 and was knighted in 1577. He discovered the Throckmorton Plot and the Babington Plot. Walsingham died April 6, 1590 at Barn Elms in southwest London.

Sir Thomas Walsingham (1561-1630) was an important landowner and literary patron.

Ingram Frizer was employed by Walsingham, at Scadbury Manor before he killed Christopher Marlowe. Walsingham may have allowed Marlowe to live at one of the many houses he inherited. Marlowe and Walsingham were friends during this time. Walsingham died in August 1630 and was buried in Chislehurst, Kent, England.

Thomas Watson (1555/1557-1592) was an English poet and author of The Hekatompathia, or Passionate Century of Love.

Watson and Christopher Marlowe were arrested and incarcerated at Newgate Prison for the murder of William Bradley. Marlowe was released after two weeks, while Watson stayed six months longer. Watson wrote An Eclogue upon the Death of the Right Honourable Sir Francis Walsingham in 1592. His second Latin epic Amintae Gaudia was published posthumously by “CM,” who many believe was Christopher Marlowe. Watson is buried at the Church of St. Bartholomew the Less in London.